- Home

- Lucy Burningham

My Beer Year

My Beer Year Read online

Sign up to receive free projects and special offers from Roost Books.

Or visit us online to sign up at roostbooks.com/eroost.

Roost Books

An imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

roostbooks.com

©2016 by Lucy Burningham

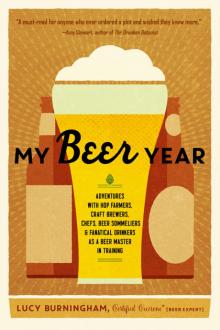

Cover art by Egor Zaharov/colourbox.com and mart/provector/shutterstock. Cover design by Daniel Urban-Brown.

Beer Tasting Sheet by Rob Hill, Certified Cicerone®, copyright © 2010 by Total Wine & More, reprinted by permission of the author. Craft Brew Alliance Sensory Ballot reprinted by permission of the Craft Brew Alliance.

The Credits section constitutes a continuation of the copyright page.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Burningham, Lucy, author.

Title: My beer year: adventures with hop farmers, craft brewers, chefs, beer sommeliers, and fanatical drinkers as a beer master in training / Lucy Burningham.

Description: First edition. | Boulder : Roost Books, an imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc., [2016] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016010941 | eISBN: 978-0-8348-4053-9 | ISBN 9781611802719 (pbk.: acid-free paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Brewers—Biography. | Beer industry—Biography. | Beer. | Burningham, Lucy—Travel.

Classification: LCC TP573.5.A1 B87 2016 | DDC 338.4/766342—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016010941

FOR TONY

CONTENTS

Prologue

1. Homebrewed

2. Palate Pushing

3. Hop Hunt

4. Join the Crowd

5. Contained and Drained

6. Sugar Rush

7. Going Wild

8. Unbroken Chain

9. Perfect Pairings

10. A Little Rock ’n’ Roll

11. Judgment Day

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Beer Tasting Sheet

Craft Brew Alliance Sensory Validation Ballot

Further Reading: A Beer Master’s Bookshelf

Resources

Credits

Index

About the Author

E-mail Sign-Up

PROLOGUE

You can, you should, and if you’re brave enough to start, you will.

—STEPHEN KING

ONE SPRING DAY, I stood in my kitchen and poured a bottle of India Pale Ale into a pint glass with the habitualness of someone making coffee or chopping an onion. Since I’d moved to Portland, Oregon, drinking craft beer had become a common ritual for me, but something about this ale seemed out of the ordinary. It demanded my full attention, starting with its vibrant orange hue and intermittent bubbles that pressed to the surface in neat lines like a festive Cava. As I finished pouring, a compact layer of creamy foam materialized on top. The beer smelled like a tangerine peel in the dead of winter, and the white head reminded me of citrus pith. I took a sip, and a spike of bitterness eased into warm earth and crushed blossoms. Something complicated was happening, a song between the beer and my senses.

Years later, I would think of that beer and regret that I didn’t know much about it. I was the prince at the ball, and the beer snuck away before midnight. I didn’t know its name, where it was brewed, or its alcohol content by volume. I didn’t know what varieties of hops created the floral aromas or during which phase of brewing they were added. I didn’t know where those hops were grown or who had bred them. I didn’t know what was in the grain bill or how the brewer had kept the yeast healthy. I didn’t know if I’d met the brewer or set foot in the brewery where the beer was made. I didn’t know whether the beer had won any medals or, instead, had slipped into the canon of unspectacular ales that no one cared about except for me. I didn’t know if it had traveled in a refrigerated truck during a heat wave or a container ship during an ice storm. I didn’t know whether the beer was inspired by tears or love, the profound or the mundane. Mostly, I didn’t know why I liked it so much.

Even though beer is one of the world’s most ubiquitous beverages, at the time I had just begun to find it fascinating. Archeologists believe humans have been making beer since about 7000 B.C.E., a few thousand years after our ancestors started farming grains. In the modern world, the liquid sloshes inside ceramic pitchers on dinner tables in France and weights aluminum cans in Japanese vending machines. It’s made over fires outside of South African houses. Beer is a staple, a social lubricant, a safe alternative to questionable water, and an object of worship. It lives in barrels, travels through tubes, burps and foams in kitchens, and explodes in heated rooms.

In 2005 I moved to Portland, Oregon, with my then-boyfriend, Tony. Right away, we took up a new hobby: sampling the multitude of beers brewed in our new town. How could we resist? Most Portlanders talked about beer with the passion and intensity of crazed sports fans, the kinds who sleep in jerseys and battle with depression after their team loses the championship. These beer fans rattled off stats, from International Bitterness Units to original gravities. They knew brewers’ nicknames and resumes. They spent weekends visiting obscure breweries they guessed would become the next big thing. They spread rumors about infections and defections. They were possessed by something I couldn’t understand that transcended flavor and taste. Together, the beer and the people formed a unique symbiotic relationship, which forced me to entertain what seemed like a radical thought at the time: beer is an expression of place.

Being interested in beer was a slightly improbable turn of events for someone from Salt Lake City, Utah. I hardly knew about the drink growing up. Until I was a teenager, my parents didn’t drink alcohol, so I never saw a single beer in our fridge. I had my first beer in high school, something skunky in a bottle, which I drank while watching a Bob Marley video in a basement rec room. Even before I was of legal drinking age, I resented how the beer sold in Utah grocery stores and gas stations was “watered down” (the law mandates 4 percent or less alcohol by volume). You could buy “real” beer with higher alcohol contents through state-run liquor stores, places that felt threatening to those of us with fake IDs. Besides, the liquor-store beer was expensive and stored at room temperature; you really had to plan ahead to have a cold one. One sound will always remind me of Utah beer: When Tony and I started dating, we developed an unspoken ban on drinking craft beer at home, an extravagance we chose not to afford. Instead we’d buy eighteen-packs of Busch from the grocery store. Tony would dump the cans into the refrigerator crisper drawer that never held vegetables, a percussive moment that was frequently followed by the pssst of a can being opened. In Utah, kegs were illegal, so I never went to keggers, nor saw anyone do a keg stand. Instead, I heard stories of people being pulled over and ticketed for having kegs in their car on the way back from Wyoming.

The summer I was nineteen years old, I worked as a busser in a restaurant in a canyon in Salt Lake City. The restaurant’s only beer on tap was a locally brewed raspberry wheat ale that tasted like artificial candy. I secretly sipped the beer between bus-tub hauls of egg-smeared plates and empty coffee mugs, and I would smell a strange iteration of fruit seeping from my pores after a long shift.

I had my first dark beer on a brisk fall night in Missoula, Montana, inside my friend Garrett’s apartment a few blocks from the train tracks. Not only did the label of the Samuel Smith Oatmeal Stout look sophisticated, like our conversations about literature (we were English maj

ors, after all), but in our glasses the beer—black, opaque, and enigmatic—looked sophisticated too. With one silky sip, I felt like I’d been initiated into a secret club. This was only a few weeks after my mom had come to visit and, at a place that served pizza with exotic toppings like mango and prosciutto, she’d ordered a beer named Moose Drool solely because of the name. When the beer touched her lips, she had closed her eyes and smiled serenely. It was the first time I saw someone derive such pure pleasure from a pint.

One summer during the late nineties, I left Missoula to live in San Francisco, where I worked as an intern and receptionist for the city’s regional magazine. I was assigned to work on the food section, which felt unlucky: I thought of myself as a hard news journalist, and reporting on food seemed fluffy by comparison. But soon I was eating dim sum and raw oysters for the first time, and the job didn’t seem so bad. At one point, the two food editors invited me to join them for dinner at Zuni Cafe, which they were reviewing for an upcoming issue. When it came time to order an aperitif that would precede the café’s famous roast chicken, I politely ordered a beer. “I would not have asked for a beer right now,” said one of the editors disapprovingly, as she pinched the stem of a glass of white wine. But you are not me, I thought.

In Portland, I couldn’t ignore my fascination with beer. Because I was working as a freelance writer, I pitched stories about things that interested me, from truffles to bicycle touring, and soon I was writing more and more stories about beer. In 2014 I realized I’d been writing about beer for seven years. I’d visited hop farms and breweries, and I’d been to a party where people shared thousands of dollars’ worth of rare beer. Once, I ended up in the basement of a Brooklyn beer bar, where a taxidermied squirrel had its arms wrapped around a Belgian ale—a koozie unlike any other. Along the way, Tony and I had gotten married, bought a house, and had our son, Oscar. I found myself in my late thirties longing for a different relationship with beer. I wanted more. I wanted to move from someone who observed beer as an outsider to someone who knew beer from the inside. I considered myself a generalist, so this desire felt foreign. I’d never wanted to go deep into any subject, but there was something different about beer. Beer made me want to play scientist, to understand the lifecycle of yeast. I wanted to be able to identify hop varieties by scent alone and to become a historian who could recite tales of German immigrants in the United States.

One day, a friend asked me if I planned to become a Certified Cicerone, which I understood to be a beer sommelier, someone who could speak with authority about brewing techniques and beer history while properly pouring beer into the right glassware. Her question got me thinking. What if becoming a Certified Cicerone could help me undergo the kind of beer metamorphosis I craved? Studying could help me learn about beer with depth and focus, and committing to taking the certification test would give me a deadline, a pressing reason to make beer the centerpiece of my life for a set amount of time.

In many ways, the Cicerone Certification Program was like a wobbling toddler, still learning how to walk; on the timeline of American craft beer, the program was new. Beer educator and author Ray Daniels launched the Cicerone program in 2008 in response to a problem he’d noticed during the early 2000s: a flood of bad beer.

“There was good beer available, but the people serving it were utterly ignorant about beer, how to care for it and present it,” he told me over the phone. A certification program that inspired proper training, Ray reasoned, would ultimately lead to a cavalry of servers treating beer with respect, and as a result, more people would drink better beer. The idea of trained beer-service professionals ran counter to how most Americans conceive of the drink.

“In our culture, we tend to think of beer as extremely simple,” he said. “You pick up a bottle of beer, pop the top off, and drink it. What could be any simpler?” But, he went on to say, beer is complicated. For one, it’s perishable like bread. And it’s dispensed in ways that can alter its flavor, texture, and aroma.

Ray named the program Cicerone (pronounced sis-uh-rone, or chee-cha-rone if you’re Italian), because it means “guide.” The word derives from Cicero, the famous Roman orator. In Italy, cicerones are informed locals who speak to the history and integrity of a place, especially as tourist guides. The writer Henry James referred to cicerones in many of his works about Brits visiting Italy. For example, he said one of his characters was like a cicerone when he provided a “bird’s-eye view” of his early years abroad. When I told my Italian friend Ciro about the title of cicerone, he said, “In Italy, we would say you speak for the beer.”

Much like the Court of Master Sommeliers program for wine, the Certified Cicerone program offers different levels of certification. Each level requires a certain depth of understanding of beer styles, brewing techniques, beer ingredients, tasting, serving, and food pairings. The first-level exam is an accessible online multiple-choice test, while the Master Cicerone certification anchors the other end of the spectrum. There are only 11 Master Cicerones, which means 109 people have taken the Master exam since 2008 and not passed. The grueling two-day exam includes tasting and describing the technicalities, characteristics, and history of certain beers for a panel of beer-industry luminaries.

I wanted to become a Certified Cicerone, which at the time was the middle level, one below Master. (Since I’ve taken the exam, an Advanced Cicerone level has been added between the two.) It wouldn’t be easy. Only about 40 percent of people who take the test pass on their first try, a lower passing rate than most bar exams. The test takes four to five hours to complete and has three parts: a written portion with fill-in-the-blank and essay questions, a tasting section that requires test takers to blind taste and evaluate beers, and a demonstration section, during which test takers prove they can operate draft equipment and properly pour a beer. The tests take place at headquarters of beer distributors, hotels, culinary schools, restaurants, bars, and breweries in most major U.S. cities (plus a few in Canada, Australia, Ireland, and the United Kingdom).

While the Cicerone program offers a few five-day study camps in Chicago every year (for an investment of $1,995), most aspiring Cicerones study on their own, starting with the program’s detailed syllabus and other official suggestions: recommended reading, tasting webinars, other certification programs, courses, apps, flashcards, and the recommendation to brew beer on an amateur or professional scale. That makes signing up for the exam the easiest part. The studying and prep? Good luck, the site whispers between the lines. Let us know how it goes.

Today, there are about 2,000 Certified Cicerones, many of whom pour, analyze, and educate the masses about beer as sommeliers, brewery consultants, festival organizers, authors, and teachers. Ray told me he considers Certified Cicerones “mature” beer professionals. “They’re people you could give the keys to a beer program and they’d be able to operate unsupervised.”

He recommends that people like me, who don’t work in the beer industry, take a year and a half to study and prepare for the exam. After all, there’s a lot of material to cover: hundreds of beer styles, the mechanics of draft systems, the chemistry of ingredients like hops, and beer’s ancient history. Plus, the tasting section requires a unique kind of new muscle: the ability to conduct proper sensory evaluations, which takes time to develop.

I looked at a calendar. If I started studying in June, I might be ready to take the Cicerone exam the following spring. I could begin by focusing on brewing and ingredients. I’d make some homebrew and spend some time helping pros in commercial breweries. During the late summer, I’d visit hop farms during the harvest to learn about one of my favorite beer ingredients. In October, I’d go to the Great American Beer Festival in Denver, where I’d have access to every beer style imaginable, as well as the brewers who made them. Winter would be a good time to learn about draft systems and beer styles. And theoretically, I could squeeze in a trip to Europe, where I could learn about historical brewing traditions. By the time I received my test results, I w

ould have experienced one whole year of beer immersion.

Even though I was shaving months off Ray Daniels’s recommended study time, the plan felt necessary. Ever since I’d given birth to Oscar, who was now four years old, I’d come to understand time in that cliché way that’s most obvious on birthdays and first days of school. There would never be a convenient time to study for the Cicerone exam. At least I liked being a student, I thought to myself as I scrolled through the Certified Cicerone syllabus, which began with a breakdown of the three-tier system for alcohol sales in the United States and ended with India pale ale as an ingredient in salad dressing.

The syllabus revealed I would need to set aside a lot of time for studying. While I certainly wasn’t the first parent to sign up for a challenge while raising a small child, I was already feeling stretched by writing deadlines, which I carefully wedged around preschool hours, nap times, and healthy home-cooked meals. Tony owned a custom bicycle business, a demanding and stressful job that was a slippery component of our collective juggling act. I’d already come to terms with the fact that I wasn’t a person who could go to every beer festival and bottle-release party. Being a working mom meant I had less access to the scene and, more important, to the beer. In some ways, that distance could help me. I already knew getting blotto and nursing hangovers isn’t conducive to retaining information, which presented an interesting paradox: to pull this off, to become a Certified Cicerone, I’d need to approach beer—commonly consumed to blur and loosen the grip of perception—with my most sharpened senses.

Once, a woman in Chicago asked me to reveal my beer ah-ha moment, the time when one beer permanently changed the way I look at beer. I told her about the IPA in my kitchen, but it didn’t seem like the right answer, mostly because I didn’t believe in the question. For me, beer ah-has are more like Buddhist prayer beads. Not only are the moments connected, they inevitably lead back to each other. On the verge of a journey I hoped would deepen my understanding of beer, I wondered what experiences would slide into my fingers. Would my quest for knowledge reveal more mystery, romance, and allure or send me in the opposite direction, toward a more practical and mechanical understanding of beer? There was only one way to find out.

My Beer Year

My Beer Year